Once the immediate danger has passed and floodwaters recede, survivors enter a challenging phase of recovery. Floods in Nigeria. Post-disaster recovery in Nigeria. This period can last weeks, months, or even years. In Nigeria, the post-disaster reality often exposes systemic gaps that make rebuilding lives difficult. Understand Nigeria’s post-disaster reality, from governance gaps to climate change impact, and how better environmental management can aid recovery.

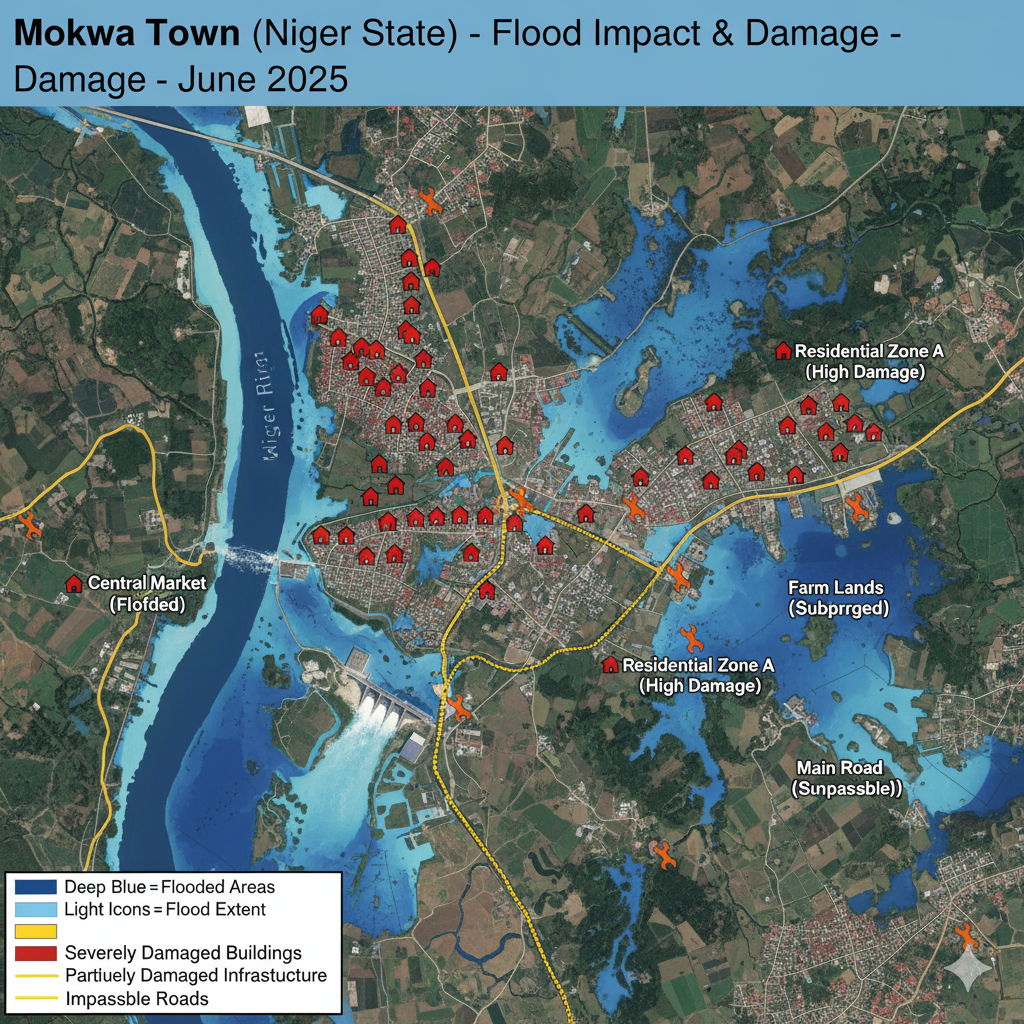

Damage Assessment: In the wake of a disaster, officials and humanitarian groups conduct surveys to quantify the destruction. They count homes destroyed, infrastructure damaged, and lives affected. These assessments help determine the relief and funds needed for recovery. For instance, the 2025 Mokwa floods devastated entire neighborhoods, reports showed more than 4,000 houses destroyed and over 600 people missing. Farms and businesses were not spared either, wiping out livelihoods overnight. Such staggering losses, documented in post-incident reports, paint a clear picture of how much rebuilding must be done. Yet, conducting thorough assessments can take time, and initial numbers are sometimes far below the actual damage, leading to later revisions as more information comes in.

Shelter & Living Conditions: In the short term, many displaced families live in temporary camps or public buildings turned into makeshift shelters. Unfortunately, conditions in these places are often dire. Basic amenities like clean water, toilets, and electricity are frequently insufficient. Overcrowding is common, as seen in Mokwa’s camps where thousands crammed into facilities meant for a few hundred. Not surprisingly, health and hygiene suffer from dirty, stagnant water and poor sanitation in camps increase the risk of disease outbreaks. Frustrated and exhausted, some survivors described the camps as “unfit for human habitation,” citing the lack of water, toilets, and medical supplies. Such conditions add insult to injury: people who just lost their homes now face the threat of illnesses like cholera in the very shelters supposed to protect them.

Governance & Accountability: Nigeria has dedicated funds and agencies for disaster recovery for example, the Ecological Fund, which allocates money to states for managing floods, erosion, and other ecological problems. In theory, after a disaster, there should be money available for relief and reconstruction. In practice, however, there are often serious questions about where these funds go. Oversight is weak, and affected communities rarely get a transparent accounting. After severe flooding in Borno State in 2024, for example, a prominent civil society group (the Socio-Economic Rights and Accountability Project, SERAP) urged the President to investigate how Borno’s government spent the ecological funds it had received. Such calls were fueled by suspicions that funds earmarked for flood defenses and relief projects had been mismanaged or diverted. The lack of clear accountability not only delays reconstruction (as money fails to reach projects on the ground), but also breeds mistrust. Survivors see donations pouring in and hear grand promises of aid, yet months later many are still living in rubble with little to show in terms of government assistance. Demanding accountability, through audits and public reports, is essential to ensure that relief funds benefit those in need and that lessons are learned to mitigate future disasters.

Psychosocial Toll: Beyond the physical wreckage, disasters inflict deep emotional and psychological wounds on survivors. Families mourn the dead, including loved ones who may never be found. Children can be particularly traumatized by the chaos and loss of security. In Nigeria, mental health support in disaster aftermaths is minimal, there are few counselors or social workers deployed to help people cope with trauma. Displaced individuals often feel abandoned and disoriented, having lost not just homes and belongings but their entire community network. The stress of uncertain futures, coupled with the hardship of daily life in temporary shelters, can lead to anxiety, depression, or PTSD. Unfortunately, mental health services are rarely prioritized in emergency response budgets. Survivors are left to rely on personal resilience, family, and faith to get through an extremely difficult time emotionally. This psychosocial aspect of recovery is an area with much room for improvement, as healing the mind is critical to fully restoring lives.

In summary, the post-disaster period tests a nation’s capacity for compassion and good governance just as much as the disaster tests emergency response. Transparent and equitable recovery efforts are essential to rebuild trust and resilience. Communities need to see that they have not been forgotten once the TV cameras leave. That means providing safe living conditions, getting kids back in school, restoring livelihoods, and building back infrastructure better than it was before. It also means addressing the root problems, like poor urban planning or corrupt fund management, so that the next disaster doesn’t simply repeat the cycle of destruction and frustration.

“Nigeria faces significant challenges from natural and man-made disasters, but it is actively learning from each experience to strengthen its disaster management cycle. By investing in preparedness (educating the public, empowering communities, and improving infrastructure) the country can reduce the impact of crises before they happen. When disasters do occur, a swift and coordinated response, involving both authorities and volunteer citizens, can save countless lives. And in the aftermath, a focus on accountable, people-centered recovery efforts will help survivors rebuild their lives with dignity.“